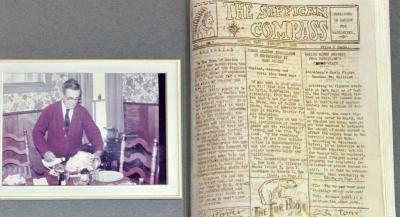

Brothers reminisce about creating the first newspaper in Marion

A local carpenter protests to the Board of Selectmen about the installation of a female lavatory in the Marion Town House. The postmaster retires. The police caution people about road hazards.

Sound like the local news? Well, it was, back in 1939 when the Sippican Compass first went to print.

"We were the first paper in Marion," said Lewis Lipsitt, a professor emeritus of psychology at Brown University and one of the three Lipsitt brothers who created the Compass with help from their father. "Wareham had the Courier, and New Bedford had the New Bedford Times. We covered Marion."

"We've been in Marion since 1938," said Paul Lipsitt, a former attorney and psychologist. "We moved here the day after the hurricane of '38. We had to wade through the water to get to our new house."

Shortly after moving to Marion, the boys decided, with help from their father, Joseph Lipsitt, a lawyer and former journalist for the New Bedford Times, to create the Compass. They did so with a $12 mimeograph machine that Don Lipsitt, the third brother involved with the Compass and now a psychiatrist, purchased at Keystone Stationary in New Bedford.

"I wheedled enough money out of Dad for the mimeograph," said Don.

A mimeograph is a machine that acts as a low-cost printing press by forcing ink through a stencil of a page. For the Lipsitts' father, the mimeograph rekindled memories of his days working for the newspaper prior to becoming a lawyer.

"My father was a newspaper man and became city editor for the New Bedford Times," said Paul. "He'd say anyone who worked for the paper had 'printer's ink' in their blood."

"I would say it was the mimeograph's presence that caused our father to be as involved as he was," said Don.

With their father taking the lead on typing and drawing for the paper's masthead, the boys covered news across Marion.

"Only Marion, but sometimes New Bedford crept in," said Lewis. "We covered all the news that was fit to print, to use a phrase."

"It was fun. We were relatively new in town and met plenty of people," said Paul. "At that time, you'd know practically everyone in town."

Marion at the time, according to the Lipsitt brothers, had a population of 1,500, only three times the number of students at Tabor Academy today.

"We sold the paper for 2 cents, and ads were 10 cents an inch," said Don. "They had them at the Marion General Store. They sold them and didn't keep any of the 2 cents."

"Once people found out about it, we started getting a lot of stories," said Don.

"People came to us. I don't remember too much running around for stories," said Lewis. "We each had a role at the paper, though. I was the Dog Editor so when a dog fell through the ice, I got that story."

Their father, of course, would pen anonymous columns under the name, "The Beachcomber," often haranguing local officials and commenting on town politics.

"He would write some racy stuff," said Paul.

To create an issue of the paper using a mimeograph machine was no trivial pursuit, however, and often took far more time and energy than covering the news.

"Our father did most of the typing and stenciling," said Paul.

"The logo on the masthead was an Indian, and it kept changing because my father would redraw it for each issue," said Don.

"The Sippican Indian on the logo was our father's tip to diversity," said Lewis.

"It'd take a couple days counting the typing," said Paul about putting the paper together using the mimeograph. "It was complicated, if you made a mistake, you'd have to cover the hole in the stencil."

The Compass printed weekly eight-page issues every Monday for 26 weeks.

By summer, the boys, according to their father, had raised enough money to go to the 1939 World's Fair.

"It ended because we went to the fair," said Lewis.

"Our father would say, oh, my boys took me to the fair," said Don.

"We covered Marion like a blanket, we said," said Paul.

The final issue of the Compass explains that the Sippican Compass has had an amazing run and that the boys would like to end it on a high note. A passage in the final issue explains that the Compass has been so successful that advertisements are being turned down in order to provide enough news coverage, a statement the Lipsitts chuckle at now.

Though the Compass came to an end, the brothers' fondness for the publication and the memories of their father endure. To this day there are issues of the Compass in the time capsule buried in front of the soldiers' monument outside the Music Hall.

"The first issue we told everyone what we were going to do," said Lewis, "and the last issue we told them that we had done it."