Marion couple share story of 'The Cowboy in Ronald Reagan's Cabinet'

Mac Baldrige, the secretary of commerce during the Reagan Administration, was different than most politicians. He liked simple language, he was an expert with compromise, and perhaps most telling of all, he was a cowboy.

Marion resident B. Jay Cooper worked alongside Baldrige as his speechwriter and director of public affairs from Baldrige’s appointment in 1981 until his untimely death in 1987.

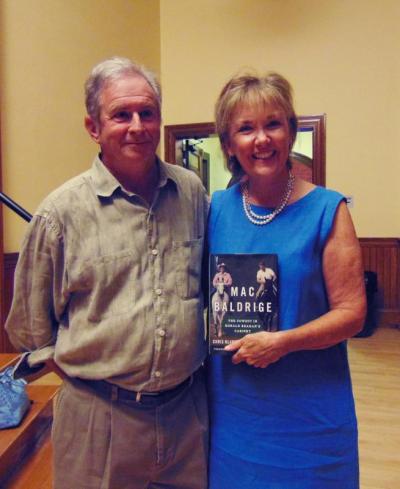

Cooper and his wife Chris Black spoke at the Marion Music Hall on Thursday evening about Baldrige and his time as secretary of commerce.

Black was a political reporter for more than 30 years, working for the Boston Globe and as a White House and congressional correspondent for CNN.

Together, the couple wrote the book “Mac Baldrige: The Cowboy in Ronald Reagan’s Cabinet,” which was commissioned by Baldrige’s daughters. Only one of Baldrige’s grandchildren was born while he was alive, so his daughters wanted a way for their children to learn about his accomplishments in the Commerce Department.

To collect the information needed for a complete picture of Baldrige’s time with the Reagan Administration, Cooper and Black relied on two sources of information: Baldrige’s former staff and scrapbooks from Baldrige’s widow.

“It was about three hundred pounds of huge scrapbooks,” Black said. “It was a day-by-day news account of his life, starting from 1980.”

Despite working with Baldrige for the duration of his career in the Commerce Department, Cooper didn’t want to rely on his memory to paint an accurate picture.

“At our age, we can’t remember what we had for breakfast,” Cooper joked.

Black and Cooper paint a picture of a quiet but candid man.

“Mac didn’t talk for the sake of talking,” Cooper said. “He would just listen [during cabinet meetings], and would summarize arguments with pros and cons and then suggest a compromised decision that Reagan would be comfortable with.”

Baldrige was also a card-carrying cowboy as a member of the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association. In order to remain a member, Baldrige had to earn money in roping contests.

“He would practice roping people in the office,” Cooper said. “Just around the legs though, never around the neck.”

His equestrian hobbies were also the reason Reagan warmed up to him.

Cooper told the story of the first time Reagan called Baldrige’s home. When Baldrige’s wife answered and told him that Baldrige was out riding his horse, Reagan said he would call back, hung up and said to himself, “that’s my kind of man.”

Baldrige, in addition to being a cowboy, was a businessman. He was largely the driving force behind the free trade policy during the Reagan Administration.

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, the United States was in great economic shape. Japan, Europe and the Soviet War had been destroyed during the war, and the U.S. had no economic competitors.

However, by 1981 when Reagan took over, Europe and Japan had recovered and rebuilt and were surpassing the U.S. economically and industrially.

Cooper and Black use the car industry as an example in the book to show how the economic power had shifted and how Baldrige was able to navigate a compromise to let the U.S catch up.

While American car companies were producing large, gas guzzling vehicles, the Japanese had begun putting out smaller cars which could last a week on a single tank of gas.

To give the U.S a chance to gain some ground, Baldrige figured out a way to convince the Japanese to hold back on the number of cars they were sending to the U.S.

Baldrige had fought with the Army in the Battle of Okinawa during World War II, and his insight to Japan was an asset to this compromise.

“Mac found the sweet spot between protectionism and no regulation,” Black said. “He had an understanding of Japanese culture without any lingering bitterness.”

He developed fair trade to help buy the U.S. industries some time, but to also force them into the future.

“It took a lot of skill and sensitivity,” Black said.

Cooper and Black’s book was commissioned about two years ago and published last November.

The pair said the grandchildren loved it, and were able to meet people who had known and worked with their grandfather at the book release party.

“We told [the grandchildren] we thought of them while writing every page,” Black said. “We had to recreate an entire era.”

The talk was hosted by the Sippican Historical Society.