91-year-old 'Negro' soldier recalls WWII service

Julio Teixeira wasn’t surprised to get a draft letter when he turned 18. It was 1943 and World War II was still going strong across the pond.

The middle child in a large Cape Verdean family, Teixeira had several brothers go to war before him. Still, the thought of getting on a boat, much less going to the state capital was daunting for the small town Marion youth.

“I didn’t even go to Boston at that age, and all of a sudden I’m overseas,” said Teixeira.

Although he is now 91, Teixeira can still remember the cry of German bombs overhead, the sight of his friend stepping on a landmine and the water pooling under him in a poorly dug foxhole on the Normandy beachhead.

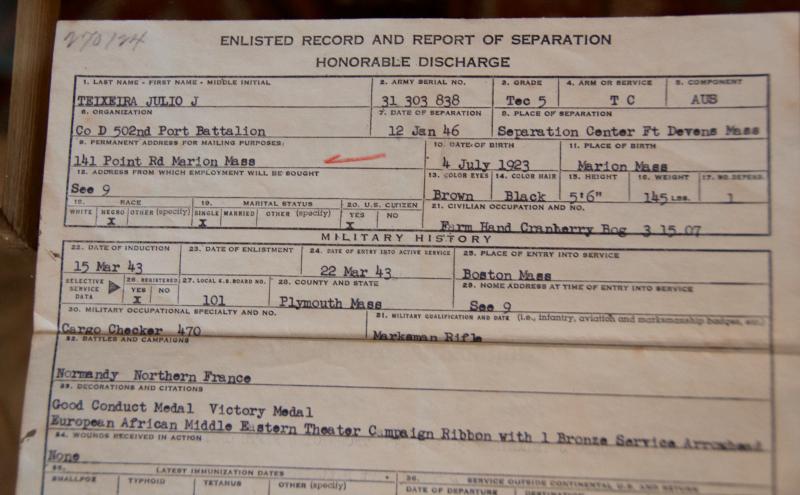

Teixeira, a first generation American, grew up speaking Kriolu at home. When it came to identifying his race on the Army application, Teixeira and his fellow Cape Verdean-American friends had two choices, neither of which really fit.

“We knew we weren’t white, but we weren’t black either,” he said.

On the advice of his brother, Teixeira marked ‘Negro’ on the form and was put in an all African-American company. After a few months of basic training, Teixeira found himself in New York City, unaware he was boarding “The Queen Elizabeth” at night.

“I didn’t know I was on a boat. The boat was so big, we didn’t know it was a boat,” said Teixeira. “We woke up in the morning – all water.”

That was just the beginning of new experiences the 18-year-old Teixeira would have during his two years, two months and 23 days of foreign service.

Teixeira spent much of his time during the war in the French port city Le Havre. As a checker, he helped unload the ships that came into Le Havre and kept track of the ammunition, food and supplies.

“We didn’t think we were going to fight really. We were going to just help out,” Teixeira said.

His company wasn’t far removed from the fighting, however. Teixeira said on D+1, the day after the Normandy invasion, the New England outfit landed on the same beach with bullets whizzing overhead and treacherous landmines still hidden all along the landscape.

“When a person in our outfit would walk, wherever he put his feet I put my feet,” he said.

Teixeira was right to be cautious. While he sat in a wet foxhole, a friend from Mattapoisett stepped out of a neighboring hole and stepped on a mine.

“I saw his leg go up in the air,” Teixeira recalled. “I went to him but I didn’t look down.”

His friend survived the mine and was sent home, something Teixeira longed for himself. He often thought of Marion and imagined familiar places, people and food while the sound of German bombs screeched overhead.

“You don’t know where it’s going to. You sit there and pray,” he said.

The fact that other Cape Verdean-Americans from home were in his outfit helped him feel less homesick. The Cape Verdean contingent was a minority in the otherwise all black group, and often turned heads when they spoke Kriolu.

Teixeira enjoyed getting to know the people in his division.

“We didn’t have many black people around here,” he said, speaking of Marion. “I was glad we got to know them.”

Teixeira still speaks on a weekly basis with a friend from his company who lives in New York.

“All this time we’ve still been friends,” he said.

And Teixeira said the battalion was treated well.

Of the white officers he said, “They don’t hug you, but they’re alright. They didn’t call names on you.”

He also got a warm welcome from the French and English, and when on furlough, traveled to some of Europe’s great cities.

In Paris, Teixeira got a photo in front of the Arc de Triomphe and while in London he saw some famous Brits when he and his friend came across a group of people waiting by a car.

“Wait here. You never know, it might be somebody important,” Teixeira told his friend. “It was the queen and king. They stood and waved.”

That was a memorable experience, so was English cuisine, though for a different reason.

“I ordered a chicken. It was gray. It looks like a seagull,” he said.

On such occasions, Teixeira longed for a plate of jag, Cape Verdean rice and beans, from home.

Teixeira finally got his wish to go home in 1946, after more than two years overseas.

Once back in Marion, he got technical training learning to sew through the GI Bill at a New Bedford factory. Teixeira worked for 40 years before retiring, 20 years stitching luggage and another 20 years finishing rugs.

Never married, Teixeira still lives in Marion, where he often sees family and friends. He frequently thinks about his time during the war and wishes he had made it back to Le Havre and the Normandy beach.

“I’m too old now,” he said.

It was a difficult two years, but his attitude was like many of the time, “I’m doing this for the country. We all have to do it.”

The experience taught him a lot, said Teixeira.

“I’m glad I went.”