Nitrogen numbers stay level in Buzzards Bay, report finds

A recent report shows that nitrogen pollution has leveled off in Buzzards Bay, but Mark Rasmussen, president of the Buzzards Bay Coalition, says the tri-town and other towns in the watershed still have work to do.

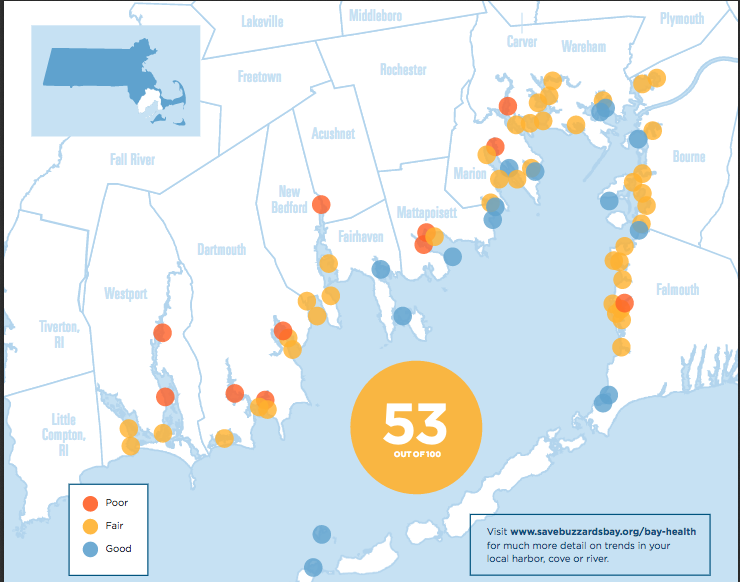

The Buzzards Bay Coalition’s State of Buzzards Bay report is published every four years and assesses the health of the bay, from Little Compton, Rhode Island to the Cape and islands, using data collected from harbors, rivers and coves. On a scale from zero (worst) to 100 (best), the report analyzes three categories: pollution, watershed health and living resources. Based on the scores, which are also in three categories: poor, fair and good.

For the 2011 to 2015 report, the overall score for Buzzards Bay was 45, the same score as the 2007 and 2011 reports, versus 48 in 2003.

Within the 45 score is a 53 for nitrogen pollution, the same as 2011, which was a drop from 56 in 2007 and 59 in 2003. The fact that the figure has remained steady across eight years is a good sign, Rasmussen said.

Why is nitrogen pollution such a big deal? Nitrogen comes from human wastewater and fertilizers, and when it ends up in the bay in large amounts, it “over fertilizes the bay.” Algae blooms on the surface, shutting out light to plants that grow below and reducing the oxygen in the water, thereby choking fish and shellfish.

“It literally sucks the life out of the bay,” Rasmussen said.

The fact that the amount of nitrogen in the bay hasn’t increased is no accident. Federal clean air laws have resulted in a drop in exhaust from cars and power plants, equaling less acid rain that ends up in the water, Rasmussen explained.

Some towns in the watershed have worked to move households from septic systems to municipal sewer. Unlike most septic systems, sewers treat waste to remove some of the nitrogen before discharging it.

Nearby in Wareham, owners of properties located within a certain distance of waterways are required to upgrade to nitrogen-reducing septic systems if municipal sewer is not available. Those systems are pricier than the typical Title 5 systems, but are more effective in reducing the nitrogen that ultimately makes it to the bay.

While numbers have improved in some areas of the bay, others have fallen or remained consistent, and it tends to correspond to septic use, according to Rasmussen.

“We’re not seeing uniform improvement across the bay,” said Rasmussen. “What’s happening inside that number is lots of places got worse, others got better.”

Sippican Harbor in Marion didn’t change much with scores of 51 and 64 for inner and outer harbor, respectively.

Aucoot Cove, which lies in Mattapoisett and Marion, is one area where the numbers continue to be low due to septic systems as well as discharge from the Marion Wastewater Treatment Plant. The inner Aucoot Cove has rebounded some since 2012 when the number was in the low 30s. The current score is 39, which brought it from poor to fair.

Rasmussen said the score could improve further if the treatment plant removed more nitrogen.

“It’s a lot easier for a community to upgrade a wastewater treatment plant than to bring thousands of houses off septic,” he said.

Mattapoisett Town Administrator Mike Gagne said the town is also looking at ways to reduce pollution in Aucoot Cove and is two months into a grant program that will address those concerns.

The mouth of the Mattapoisett River is an area that has seen a drop in water health. The current score is 34, the lowest it’s been since the Coalition began reporting data in 1992.

Such a low number means something is happening farther up the river. The head of the Mattapoisett and Sippican rivers are in Rochester, which has no municipal sewer but does have a number of commercial cranberry bogs that can leach fertilizer into waterways. Additionally, runoff from Route 6 and I-195 filters into the river.

The inner harbor of Mattapoisett showed a slight increase in health from about 61 in 2012 to the current score of 63.

That likely corresponds to efforts made by the town to reduce runoff into the harbor.

About four years ago Mattapoisett installed a stormwater discharge system on Water Street that filters out contaminates such as nitrogen and phosphorus. It's led to fewer closures at Town Beach, too.

“That was the biggest things we did for the inner harbor,” said Gagne.

Additionally, sewer extensions were installed in 2013-14 on Mattapoisett Neck Road with around 200 homes tying in, and hundreds of acres in the tri-town have been purchased and protected by the towns, the Coalition and land trusts.

Reducing contaminates in the bay isn’t free, however. Those acres cost millions of dollars, the stormwater system in Mattapoisett cost more than $100,000 and then there's the wastewater treatment plant.

Marion is already looking at federal requirements that seem likely to result in millions of dollars of upgrades, and simply extending the sewer costs hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Marion Town Administrator Paul Dawson said the town hasn’t necessarily been doing anything differently yet, but that officials have been working hard to make improvements to the system.

“We’re continuously monitoring sewer outflows and doing maintenance work,” he said. “It’s an ongoing process. It’s all about routine maintenance and upkeep, we’ve said from the beginning that is what helps.”

The costs can seem daunting at times, but towns and nonprofits in the area have been working together to improve water quality, and Rasmussen said it's an achievable goal.

“It’s a battle that can be won.”