Fewer river herring returning to the tri-town

The river herring count in the Mattapoisett and Sippican Rivers has fallen for the third time in as many years, and officials aren't quite sure why.

The endangered fish are facing a population crisis throughout the East Coast, and the tri-town is no exception.

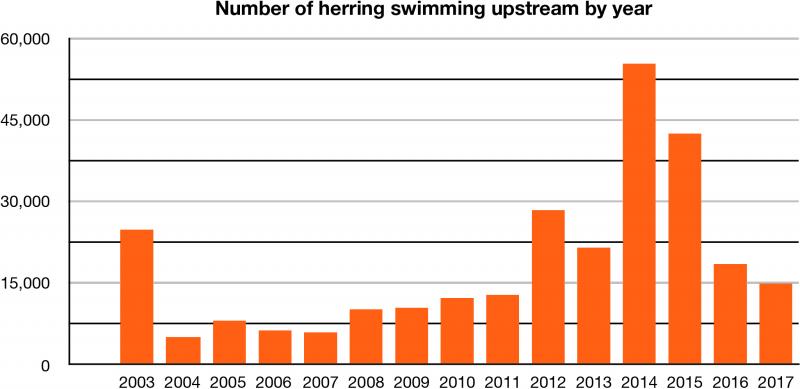

Alewives Anonymous released its herring count for 2017 recently, noting that 14,938 herring were counted swimming upstream in 2017. Founded in 1984, Alewives Anonymous works to preserve herring resources within the tri-town. The group has been monitoring the number of fish in the Mattapoisett River, using an digital counting system, since 1989.

In eras past, the river herring (a catch-all name for both alewife and blueback herring) were so numerous in the tri-town that sales of the fish paid for Rochester’s entire school system.

Then, in the early 2000s, the overall river herring population fell drastically. The Mattapoisett River’s total herring population in 2004 tallied 5,000, the lowest number since record-keeping began. The population indicated a crisis, coming just four years after a record-high population count of 130,296.

The overall loss of river herring was severe enough for the Massachusetts state government to pass a moratorium on their harvest, possession or sale in 2006. That moratorium remains in effect today.

For a brief moment, it seemed as if there was a light at the end of the tunnel. A 2014 tally of 55,429 fish in the Mattapoisett River, after several years of four-digit fish populations, seemed to indicate a strong comeback. “It seemed like a promising year,” said Alewives Anonymous president Art Benner.

It was not to last. Numbers began to dwindle again the very next year. The slippery fish, so smart that they swim down fish ladders tail-first to avoid leaping out of the water, have seemingly been avoiding the tri-town's rivers. Benner said that while the group isn't quite sure why the river herring population continues to drop, members have some ideas. The relatively dry summers and late springs over the past several years might be a factor, he said. The rivers have run quite low in recent summers, low enough that herring can't swim in them.

"Herring swim downstream to the ocean after they spawn," Benner explained, "and they always return to spawn where they themselves were born. It's almost as if they've been imprinted to that water." The young herring, he said, can't leave the pond and get to the ocean to mature if there isn't enough water in the river for them to swim in.

This creates a considerable obstacle in keeping the young fish alive. As Benner noted, "Their primary role in life is to be food for everything else." Birds, particularly cormorants, like them. Striped bass, who have seen a population spike of their own due to conservation efforts, consider them a delicacy.

If the fish have no way to get to the ocean, Benner said, there likely won't be any left in the next year.

The case of a nearby town may lend some credence to Benner's weather theory. In close-by Middleboro, the herring population is rising every year.

"They have nearly ideal conditions, with many more fish overall," Benner explained. "They have the big large spawning areas like Assawompsett Pond and they always have a good flow of water."

The presence of new fishing boats on the East Coast might also have had an effect on the tri-town’s river herring.

The year 2000 was the first year that midwater trawlers appeared on the East Coast, Benner said. Midwater trawlers are fishing boats that use a net to catch fish swimming in the middle of the water level, rather than at the very bottom. The nets, Benner said, can be several football fields in size.

The midwater trawlers are primarily looking for ocean herring, which are legal to catch, Benner explained. However, river herring also spend a lot of time in the cold Atlantic waters, only returning inland to breed. Young river herring spend four years in the ocean maturing, before returning to their home waters to spawn. It’s inevitable that some will end up in the trawlers’ massive nets.

"The fisherman don't want them, and they'll throw them back when they find them, but a dead fish is a dead fish," Benner said.

The moratorium on harvesting river herring is relaxed in the case of fishermen fishing in federal waters, but regulations have been placed to help protect the endangered fish. The state allows fishermen to catch a certain number of river herring in their net. Once that number is reached, the fishermen cannot fish anymore, and must return to shore. The regulations may explain a rise in river herring numbers in the Mattapoisett River between 2005 and 2014.

As it takes the fish four years to mature, Benner added, "it's also possible that something happened four or five years ago that we don't know about, and that's why we're seeing so few fish now."

Local conservation efforts have included new fish ladders and routine river cleaning. Keeping the river clean and free of debris means that fish are more likely to return, and face fewer challenges in returning. The Mattapoisett Boat Race Committee, Benner added, is the largest help in keeping the waters clean these days. “We both want a clean river,” he said. “We have mutual interests.”

Aside from maintaining the fish ladders and keeping the river clean, Benner said there was not much else to be done. “ It's the best we can do. The rest is up to Mother Nature."

Mother Nature and maybe some federal politics. The New England Fishery Council, a federal group based in Newburyport, is attempting to pass legislation which will ban midwater trawlers within 50 miles of the coast. Since river herring tend to remain closer to the shoreline, the herring would be much less likely to end up in their nets.

"We'd really like to see that come through," Benner said.

For more information about river herring in Massachusetts, visit http://www.mass.gov/eea/agencies/dfg/dfw/fish-wildlife-plants/fish/river...