Events cancelled, school disrupted: how flu changed the Tri-Town in 1918

102 years ago, churches and schools were closed and public gatherings canceled because of an illness. In 1918, it wasn’t the coronavirus pandemic, but an influenza pandemic, commonly known as the Spanish Flu. Still, the disruptions to daily life eerily mirror those in 2020.

The 1918 Massachusetts Department of Public Health said in its Annual Report that the disease, “so occupied lay-people, physicians and health officials that ordinary routines went to pieces.”

Many initial efforts from health officials focused on educating the public.

“We have been trying in every way we could conceive to awaken in the public the sense of the preventability of communicable disease and urge them to apply their common sense to the problem,” the department wrote in its report.

The state mentioned 145,000 cases in total, but said cases were not reported until about three weeks in, so that number is inaccurate.

The flu proved similarly difficult to contain.

“Early in the beginning of the outbreak it seemed that our only hope was to prevent contact infection, and this we tried to do. Our results were negative; we did not, and in fact, could not, stem the tide of this overwhelming invasion when the foci of infection were scattered over the State with no means available to detect their presence unless, perchance, they were acutely ill,” the Department wrote.

A bulletin from the beginning of 1919 listed Marion, Mattapoisett and Rochester as having a higher rate of infection, despite the fact that most of the area south of Boston had a low case rate.

Despite that historical statement, evidence of the epidemic is difficult to find in Rochester. There is no mention of the Spanish Flu in the 1918, 1919 and 1920 reports, which show there were only a dozen or so deaths each year, mostly for the very young and very old.

Marion had a population of 1,460 per the 1910 census, but by 1918 it was likely closer to its 1920 population of 1,288. In its Town Report for that year, the Health Department wrote that the town had 255 cases of influenza, and 14 people that died of influenza or pneumonia after the flu. For context, there were 40 deaths for the whole year, and the next most common disease, measles had 15 cases.

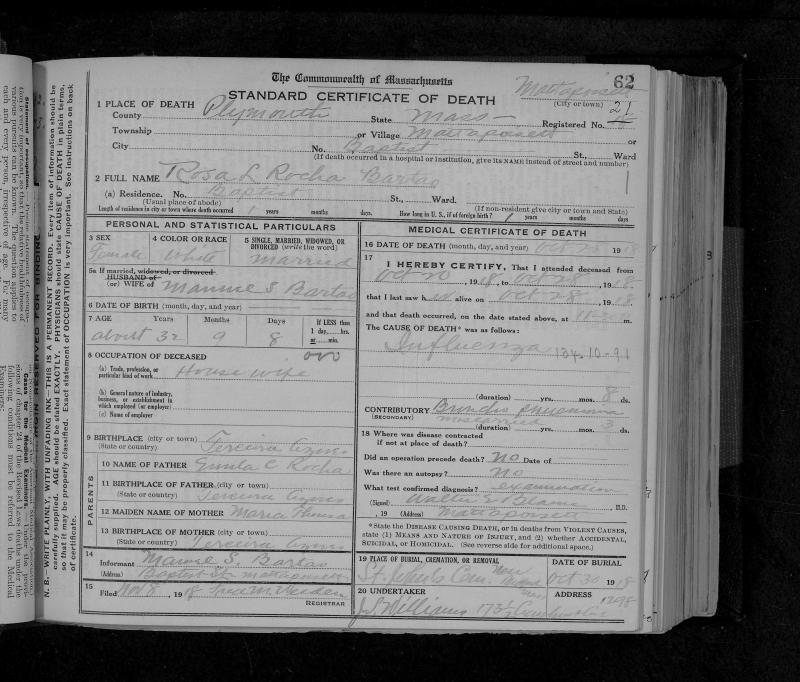

Mattapoisett, which had a population of 1,352 as of July 17, records present the clearest picture of the outbreak. Before the epidemic broke out in late September, the Town Report mentions only 28 cases of disease, most of them in children.

Then, there was a sudden spike, with 78 cases recorded from Sept. 26 to Oct. 28, though only two cases were fatal. The town also detailed a second outbreak of 62 milder cases in December.

The Boston Evening Globe reported on part of the December spike, mentioning that Mattapoisett had 35 new cases over seven days

Per the Globe, 1918 flu prevention tips included: “Keep out of crowds, beware of coughers and sneezers, get all the fresh air and sunshine possible, keep the bowels open, drink five or six glasses of water daily, don’t neglect a cold and call the doctor before illness makes any headway.

In the Marion Town Report the sewing instructor reported many interruptions to class. Other classes were cut short.

“Because of the influenza and interruptions the night school did not seem to get a fair chance this year. The attendance was small and the time seven nights short,” an unnamed educator wrote in the section on evening school.

The Mattapoisett 1918 account mentions interruptions to school as well, in a brief, slightly more optimistic tone.

“The fall term was badly broken up by epidemic conditions, but it is hoped to complete a satisfactory year’s work without lengthening the terms of school,” the report said.