Photographer recounts journey into Liberia during Ebola outbreak

As a recent college graduate with no significant photojournalism experience, Cheryl Hatch knew if she wanted to work in the world’s hotspots, she’d have to get there by herself.

So she borrowed some money, bought a plane ticket and landed in one of the most dangerous countries at the time, Liberia, in the middle of a civil war – a place where checkpoints were marked with skulls and a woman six-months pregnant might be carrying an automatic rifle.

“Liberia was my first war,” said Hatch.

It wouldn’t be her last. Throughout the 1990s, Hatch worked as an independent photojournalist in war-torn areas of the Middle East and Africa.

In December, she returned to Liberia to document the country as it faced a new battle against Ebola.

“I had a number of sketchy experience in Liberia. I wasn’t exactly sure about going back,” said Hatch, who spoke at the Friends of the Mattapoisett Library’s annual meeting.

A visiting professor at Allegheny College, Hatch and journalist Brian Castner received a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting to cover part of the travel costs for them to follow the 101st Airborne on its humanitarian mission to establish Ebola treatment clinics in each of Liberia’s 15 counties.

Like Hatch, the soldiers were used to war after tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. Now, they were receiving twice daily health screenings and were often stuck behind a wall that separated them from the Liberian people as well as a view of the Atlantic Ocean just beyond the gate.

One solider standing at the gate called the view, “a little peace of heaven.” Ironically, just north of him was a beach where 13 government leaders were executed during the civil war, said Hatch. The dangers were different now, but Hatch was not content to stay behind the wall.

“I'm not going to spend my whole trip behind the wall. We have to get out in the country,” she told Castner.

For two days, they traveled with the Liberian Red Cross, witnessing health workers covered in Tyvek suits taking away the Tyvek-wrapped bodies of those killed by the epidemic. On the other side of the spectrum, nurses at a local clinic had much less defense against the diseases, bleaching their boots and hanging them out to dry before the next shift.

Hatch also tried to get a glimpse of daily life, which was slowly returning to normal as the number of infected people lessened. During the epidemic, the bazaars were emptied and people greeted each other by tapping elbows or toes instead of embracing.

Children returning to school still read signs warning them not to touch, but people were gathering together again.

“There had been no celebration,” said Hatch. Seeing people together, she said “I took this as a good sign.”

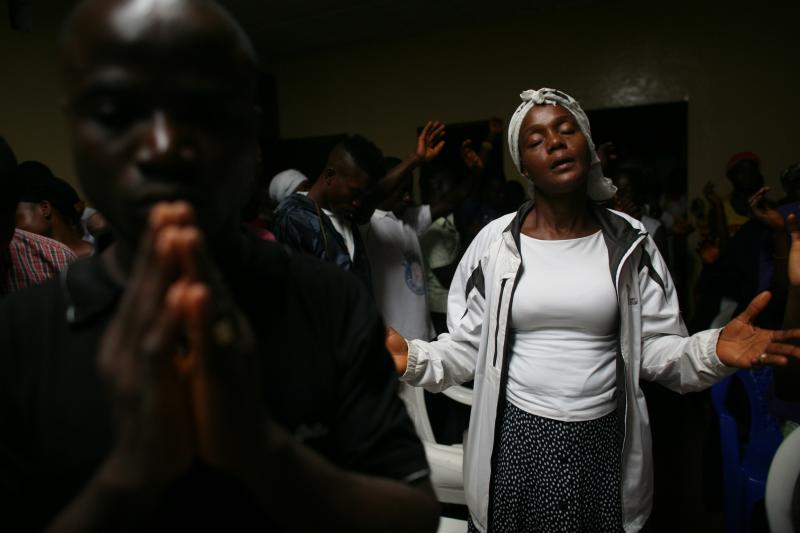

Hatch captured photos of families at the beach on New Year’s Day, and a Christian congregation, that had lost many of its leaders and members, gather for Watch Night – a time of worship as the calendar year switches over.

The church people spoke of their difficult losses as 2014 ended and looked in hope towards the future as 2015 began.

“It was an extraordinary experience. It was a beautiful example of where they’re going through and what they’ve been through,” said Hatch. “There was so always so much gratitude and faith.”

During the trip, Hatch captured these moments of heartbreak and hope, hoping to be a witness to Liberia’s people as well as the 101st Airborne.

“I do think journalism is a noble career to have,” she said. “[Journalists] are the witnesses to what’s happening.”

Since she first set out to become a journalist, Hatch says her goal has been to “make a contribution to humanity.”

Her latest contribution, along with Castner's articles appeared in VICE News, Los Angeles Review of Books and other places. Read more here. Hatch’s portfolio is at isisphoto.com (named for the Egyptian goddess). She also has a nonprofit that funds women’s education in economically challenged countries. Isis Initiative, Inc. can be found at www.isisinitiative.org.

.jpg)