Etchings of 20th-century British artist donated by Marion residents

MARION — The pieces began to mount up in the hallway of Benjamin Dunham and Wendy Rolfe’s home. The Marion residents had collected more than 170 works of Rolfe's distant relative — a British artist who during the early 20th century created etchings of European cathedrals and historical buildings.

James Alphege Brewer was the brother of Rolfe’s great-grandmother’s husband. It is that lineal thread that prompted Dunham, a retired arts administrator and journalist, to start collecting Brewer’s etchings.

“My background is in music, and I'm aware of so many stories of musicians and their compositions who are overlooked or almost completely forgotten,” Dunham said. “And I thought, well, that shouldn't happen to James Alphege Brewer, so I started to collect them.

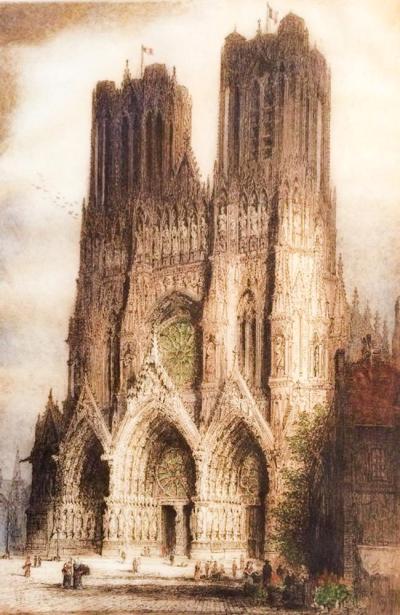

Some of Brewer’s pieces — a catalog that includes etchings of the Rheims Cathedral in France and the Ypres Cloth Hall in Belgium — were passed down to Rolfe and Dunham through family. But Dunham then looked online. He found the work of Brewer, who lived from 1881 to 1946, was available and affordable.

More than 170 acquired pieces later, Dunham is donating his collection to a trio of institutions across the country.

The College of the Holy Cross in Worcester received more than 130 etchings and related materials. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York received 21 etchings of architectural views. The National WWI Museum and Memorial in Kansas City received 26 wartime etchings.

Dunham said as his collection of Brewer’s etchings grew larger, he realized it would become a burden, if he were to pass away, on his wife and his son. He wanted the pieces to be placed somewhere they could be observed, cared for and conserved.

“The idea that they could be at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, or at Holy Cross or at the WWI Museum really pleased me greatly to know that they were going to be there long after my interest had passed away,” Dunham said.

As he collected the pieces, Dunham — perhaps “by default,” he said — became something of a James Alphege Brewer scholar. He operates a website titled jalphegebrewer.info and wrote the 2021 book “Etched in Memory: The Elevated Art of J. Alphege Brewer.”

“If an artist becomes forgotten, it's hard to reclaim them and the people who can contribute to knowledge of his work pass away, and so it’s important to get it done,” Dunham said.

Also in 2021, he gave a lecture with the Sippican Historical Society in conjunction with the exhibition of some of Brewer’s World War I etchings at the Marion Music Hall.

As he researched the life of the British artist, Dunham found that art catalogs contained incorrect dates and facts about Brewer’s history. Dunham said spoke with other family members and people who had known Brewer.

“I found out that really, his story was not only not been told, but it had been misrepresented, and so that's why I continue to collect,” Dunham said.

One of the stories of Brewer’s life Dunham gleaned was that the etcher was nicknamed “Major.” It had nothing to do with the military.

As a child, Brewer went to the London Zoo with his father. There was a chimpanzee there with a similar temperament to the young Brewer, who acted up, according to Dunham.

The chimpanzee was called “Major,” so Brewer’s father in turn called him the same. It was a nickname that stuck with Brewer for the rest of his life, Dunham said.

Brewer’s pieces are essentially drawings etched into copper or zinc with acid. The result was a real piece of art — not a photograph or a print — of which multiple copies, up to hundreds in Brewer’s case, could be produced, according to Dunham.

A pair of etchings completed in the early 20th century built Brewer’s fame abroad. The 1914 images captured the Rheims Cathedral, which would later be bombed during World War I. The etchings of the historic French building, widely reproduced and sold in the United States, acted as pieces of art expressing solidarity with the Allies, according to Dunham.

He said he’s encountered four different families who have copies of those cathedral etchings. The two etchings are included in Dunham’s 26-piece donation to the National WWI Museum and Memorial.